Ship Graveyards: Mallows Bay and Beyond

Iron hopper dredge at Garden Island Ship Graveyard, Australia. Credit: Nathan Richards

When most people think of shipwrecks, they imagine tragic disasters; sudden, unplanned events that leave behind haunting remains on the seafloor. But as maritime archaeologist Dr. Nathan Richards explains, not all shipwrecks are accidents. Some vessels are abandoned on purpose, left to decay in places known as ship graveyards. These resting places, though often forgotten, hold powerful clues about history, technology, and the evolution of seafaring culture.

In a recent Fascinated by Shipwrecks episode, Dr. Richards shared his journey from wide-eyed student in Australia to Director of the Maritime Studies Program at East Carolina University in the United States. His passion for ship abandonment began during a university field trip to Port Adelaide's Garden Island Ships’ Graveyard; a moment he says hooked him into maritime archaeology for life.

Shipwrecks vs. Ship Abandonment

Unlike dramatic sinkings, ships in graveyards were often retired after becoming obsolete, worn out, or economically unviable. Some were scuttled intentionally in deep waters, while others were simply run aground to save on disposal costs. “It’s kind of the maritime version of a garbage dump,” Richards explained. “And just like archaeologists on land study old privies and garbage pits, maritime archaeologists study these vessels to understand society’s decisions around technology and economy.”

Despite their importance, graveyards are not often the focus of mainstream archaeology. However, they’re increasingly part of environmental and development assessments. In places like New York Harbor or Mallows Bay, ships have piled up over decades, sometimes in the hundreds. These abandoned vessels can be rich sources of information and are often examined before infrastructure projects begin.

Wreck of Taifun, St. Georges Ship Graveyard, Bermuda. Credit: Dr. Nathan Richards

The Tools of the Trade

Dr. Richards also gave listeners a behind-the-scenes look at how maritime archaeologists do their work. Students in his program at East Carolina University don’t just study history, they literally dive into it. Most are trained as scientific divers, a level above recreational scuba, to operate safely and effectively in challenging environments.

From old-school tape measures to high-tech tools like side scan sonar, magnetometers, and underwater drones, the field is constantly evolving. “One of the big changes in our field is the rise of technology,” Richards said. “We’re using tools like photogrammetry and 3D modeling to preserve sites in new ways.”

There is also growing collaboration with microbiologists, particularly in studying how microbes impact shipwreck deterioration. At ECU, students work with a microbiologist to explore how microbial communities affect wood decay and metal corrosion underwater. It’s a new frontier that’s connecting archaeology with biology and conservation science.

Mallows Bay: A Living Lab

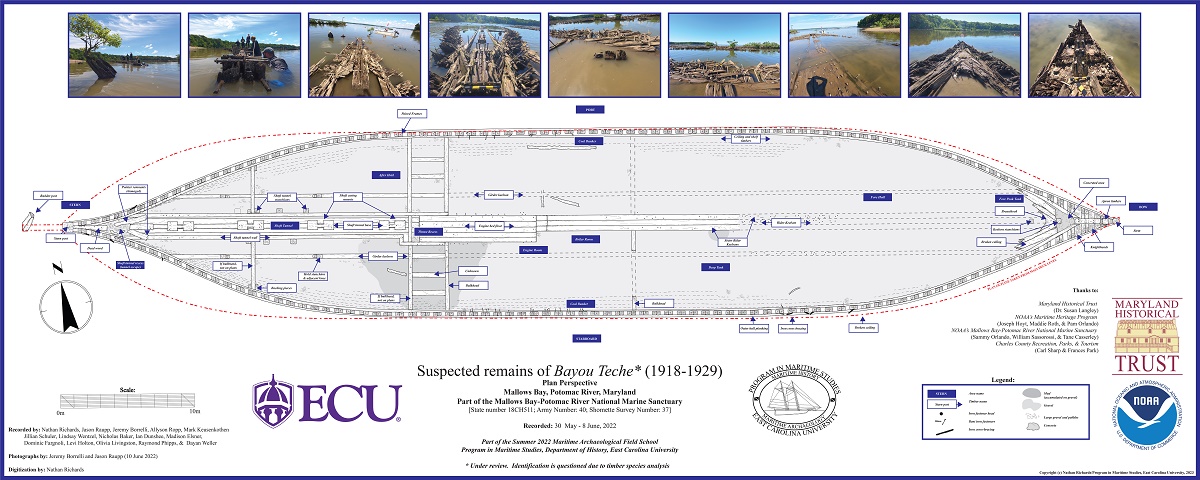

One of Richards' most active research sites is Mallows Bay, Maryland, a national marine sanctuary and one of the largest ship graveyards in the U.S. The U.S. government built nearly 200 wooden steamers to support the war effort during the First World War. When the war ended unexpectedly early, the unfinished or underused vessels were scrapped and dumped in the bay. Roughly 118 of them remain.

“These ships weren’t just abandoned, they were part of a massive economic and military decision,” said Richards. “Some were salvaged later during WWII, and now they serve as both historical artifacts and ecosystems.”

His students use Mallows Bay to practice field methods, test underwater survey tools, and expand their knowledge of microbial decay. The site has become a living lab, connecting the dots between historical maritime policy, modern conservation, and emerging technology.

What Students Learn

At East Carolina, students undergo a rigorous program focused on both academic theory and field skills. Coursework includes maritime history, archaeological theory, and specialized electives like ship construction or cultural landscapes. Fieldwork comprises a summer and fall field school where students practice on real wrecks.

Most students complete a thesis on an original research topic. Projects might involve ancient shipbuilding methods, coastal community interactions with shipwrecks, or preservation science. Richards emphasized that students shouldn’t worry about being "pigeonholed" by their thesis topics: “The skills you gain are transferable to many different areas of archaeology and heritage management.”

Students mapping amphibious gun boat from the Second World War near Rodanthe, North Carolina. Credit: East Carolina University

Career Paths Beneath the Surface

Graduates of maritime archaeology programs can find careers in various sectors. Many work in Cultural Resource Management (CRM), conducting surveys for oil and gas, offshore wind farms, or coastal construction projects to ensure heritage sites aren’t harmed. Others land jobs at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Park Service (NPS), or state-level heritage offices. Some go into museum work, conservation labs, or non-profit foundations focused on ocean history.

Not everyone needs to dive either. “There are paths for non-divers too,” said Richards. “You could be managing collections in a museum, developing virtual exhibits, or doing archival research.”

There’s Something for Everyone

If there’s one takeaway from the episode, it’s that maritime archaeology is incredibly interdisciplinary. Whether you're into science, history, tech, or art, there’s a place for you. “It’s an artistic science or a scientific art,” Richards reflected. “People come in thinking it’s one thing and end up discovering a passion for something entirely different.”

That kind of surprise and discovery mirrors the field itself. Shipwrecks, whether catastrophically lost or quietly abandoned, are more than ruins. They're portals into human history, shaped by conflict, commerce, and creativity.

Want more fascinating stories from the deep?

Catch the full interview with Dr. Nathan Richards on the Fascinated by Shipwrecks podcast. Listen or watch anytime. You'll see more photos in the video version!

© 2025 Fascinated by Shipwrecks